The Great Phone Signal Swindle

5G is still letting users down. However, a recent controversy suggests that consumers may understand phone signal even less than we had thought. Where has all the phone signal gone – or was it never really there to begin with?

5G promised gigabit speeds and reliable coverage.

For many, all it’s delivered is disappointment, and this dissatisfaction is seeping into the mainstream press.

As reported by BBC News, tests by PolicyTracker found that nearly 40% of supposed 5G connections are actually running on 4G, based on 11,000 tests across the big four phone networks in three locations in the UK.

The symbol on your phone indicates the presence of a 5G signal – but that doesn't guarantee a 5G connection. Even with 5G Standalone, users can still drop down to 4G if a faster connection is not available.

The ban on Huawei equipment from Britain's networks over security concerns has slowed the buildout of 5G masts on top of existing 4G equipment. According to Ofcom’s 2025 Mobile Matters report, only around 2% of mobile connections in the UK in the six months to March were 5G Standalone, and London ranks last among major European cities for overall mobile experience.

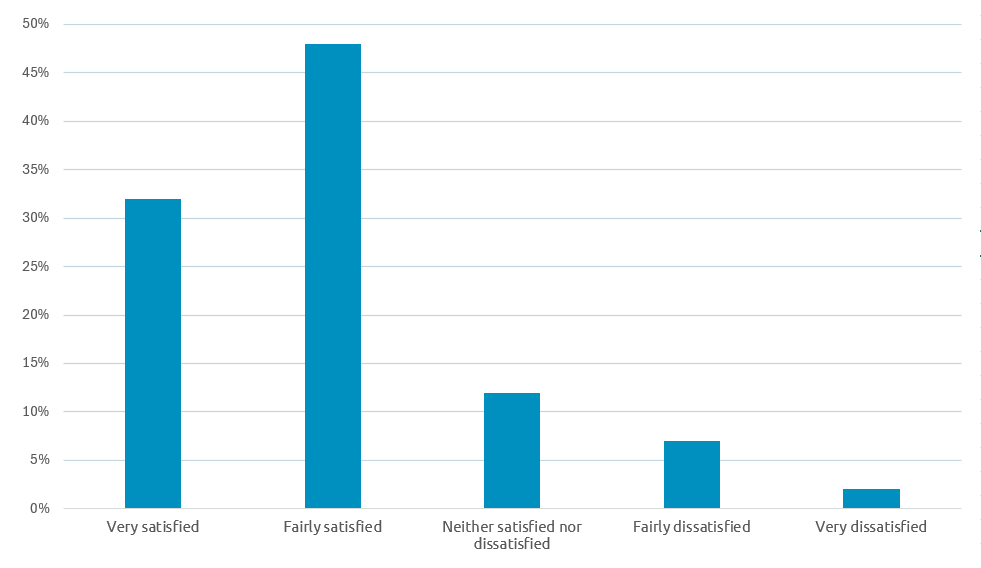

Cue widespread grumbling from users deeply dissatisfied with the state of their signal? Quite the opposite; a recent survey of 1,000 5G users in the UK found that 80% were very or fairly satisfied with speed and coverage, in defiance of the media doom and gloom:

This suggests that the narrative of widespread disappointment in 5G may be exaggerated; most consumers don’t need the blistering speeds 5G promises, with the signal speed “sweet spot” falling between 1-5Mbps.

Paradoxically, the current service is underwhelming in part because new customers aren’t demanding it, so CSPs won’t invest to fix the problems, and current customers are largely content with what they’ve got.

The alignment between technical metrics and user satisfaction is imperfect, but this mismatch between user satisfaction and actual performance isn’t new – our understanding of signal has always been flawed.

False flag

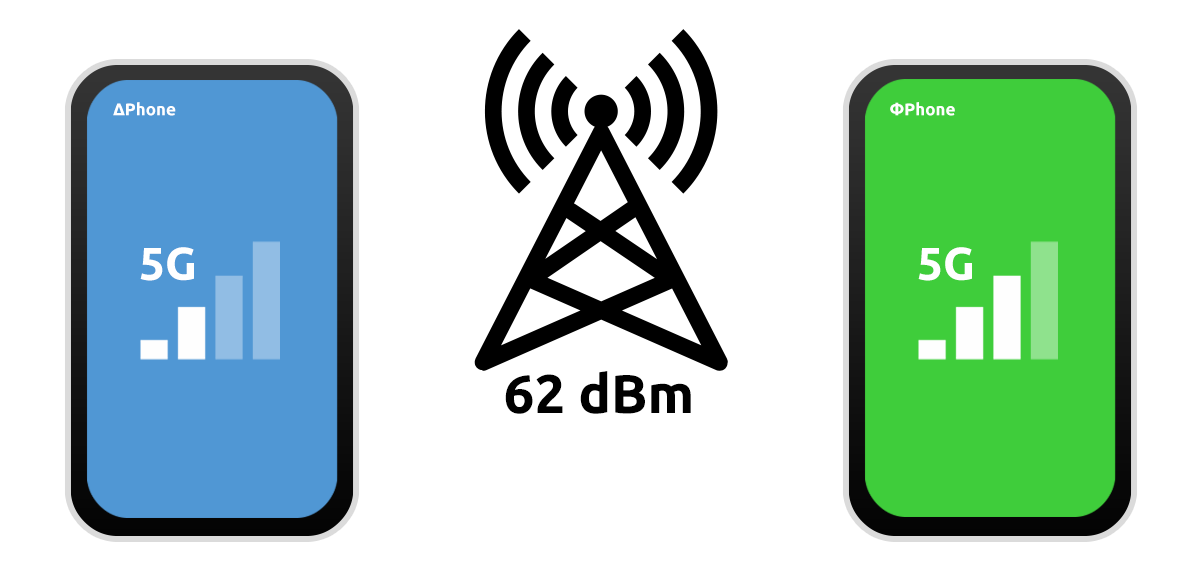

An article on Nick vs. Networking, titled “Simple trick to increase coverage: Lying to users about signal strength”, revealed that, on Android phones, the CarrierConfigManager contains a flag called KEY_INFLATE_SIGNAL_STRENGTH_BOOL that causes a device’s signal strength indicator to display one bar higher than it is.

This flag was quietly introduced in Android’s codebase back in 2017, according to the original Git Commit, but is undocumented in public Android documentation. Though disabled by default, it is readily available for carriers to activate via over-the-air (OTA) update. AT&T and Verizon are confirmed to have this flag enabled, along with some of their affiliated MVNOs.

This has no impact on actual signal quality, only changing how the UI interprets the underlying signal metrics. On a four-bar scale, that can be a 25% increase in apparent strength.

Therefore, if you’re using an Android device on either of these networks, you may see a signal indicator on your screen that doesn’t match reality.

In essence, Android has provided a mechanism for carriers to overstate how good their signal is.

A scandal in the making? Not quite.

Signal-to-noise

Speaking to Android Authority, Google has revealed that the flag was introduced after Android added a five-bar signal strength icon as an alternative to the four-bar icon, which would display zero bars even when a device had some signal.

Android’s code allows carriers to set their own thresholds for what signal levels correspond to each bar. As network signal strength bars have never been standardised, each device and carrier sets its own scale.

The unfortunate truth is that the signal bar icons on our phones are just a rough visual cue, not a direct guarantee of service quality. By adjusting the thresholds in the carrier config, an operator could choose to display four bars for a signal that might show as only three bars on another carrier’s network.

This inflation tactic has precedent, with the 3G-4G transition causing similar confusion.

For instance, Apple famously recalibrated the iPhone 4’s signal bar algorithm in 2010 after the Antennagate scandal, where users experienced significant signal loss when holding the phone in their left hand, acknowledging that the formula for calculating bar strength was “totally wrong.”

When 4G LTE rolled out, many users saw fewer bars since LTE’s signal thresholds were stricter, even though call quality and data speeds were markedly better. One or two bars of 4G signal might support fast internet and clear calls at lower signal levels that would have severely impaired 3G networks. Community forums from the early LTE era are full of users puzzled that their phone’s bars dropped despite no real change in coverage after a software update.

It led to a period of perception issues where subscribers equated low bar count with bad service, even when their 4G experience was objectively superior to past 3G performance. Carriers, not wanting fewer-bars-despite-improved-performance to become a problem, artificially boosted the signal strength visuals so that one LTE bar represented a more usable connection compared with one 3G bar.

Virtue signalling

While changing the displayed signal strength did help assuage user fears during 4G rollout, it introduced its own complications. Because these adjustments were done behind-the-scenes, users were none the wiser that the signal bar goalposts had been moved.

AT&T infamously rebranded a portion of its 4G LTE network as “5G E”, which was widely criticised as deceptive.

The number of bars shown on a phone is subjective, not an objective standard, and fewer bars on a modern network doesn’t automatically mean worse service.

User perception is instead shaped arguably more by experience than underlying technology. 4G and 5G can deliver excellent throughput and low latency even with only one or two bars, but inflating signal bars is misleading and can erode user trust and satisfaction when there is a mismatch between perception and reality.

Google has even weighed up hiding signal readings altogether “when told by carrier,” but is giving users less information really the answer?

Telcos must focus beyond the visuals on the screen – only then can they rebuild trust and deliver a mobile experience that meets expectations in both perception and performance.