The revenge of the mid-contract price rise

Shock, horror – mid-contract price rises are back! As O2 and others surprise customers with higher-than-expected increases to their contracts in 2026, is Ofcom’s once-lauded ban failing to deliver?

It seems that rumours of the end of mid-contract price rises were greatly exaggerated after O2 announced earlier this month that it would be increasing prices for customers from April 2026.

How is this possible? After all, Ofcom introduced new rules in January to crack down on mid-contract price rises for phone and broadband plans, requiring providers to set out planned increases clearly “in pounds and pence” at the point of sale.

A closer look at the original announcement holds the answer:

Ofcom bans mid-contract price rises linked to inflation.

O2 has pushed through a flat increase of £2.50 a month (£30 a year) across all plans – 40% more than the originally-promised £1.80 a month rise. Since unhappy customers can still leave without penalty within 30 days (provided their device is fully paid off), O2 is not in contravention of the rules.

Nonetheless, this move severely undermines the rules designed to improve pricing transparency and prevent unpleasant bill shocks.

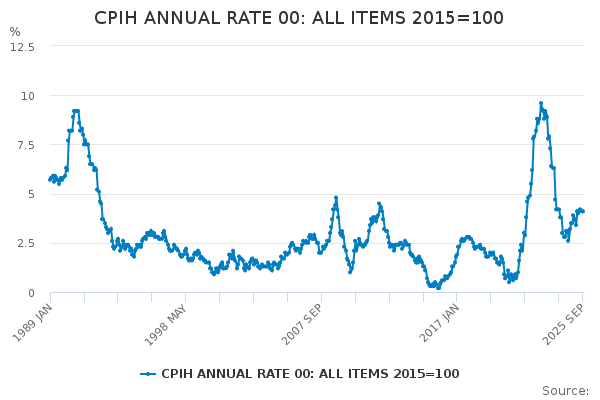

Previously, price rises were pegged annually to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), plus 3.9%. As inflation began to rise massively in 2021, peaking in October 2022 at over 11%, some mid-contract price rises were as high as 17.3%.

Now, falling inflation is reducing annual rises, though there are indications that it may be creeping up once again:

Before January 2025’s rule change, under the old pricing scheme, April’s price rises would’ve been 6.4% (CPI 2.5% + 3.9%). For O2’s 100GB tariff, currently priced at £24.00 per month, this would rise to £25.54 per month next April. Instead, it will cost £26.50, an increase of 9.43%.

As the table below shows, a flat increase of £2.50 on each plan means that customers on cheaper tariffs will end up paying more as a proportion of their total bill:

|

SIM-only Plan |

Current cost per month (2025) |

Cost (CPI* + 3.9% rule) |

Cost (April 2026, £1.80 rise) |

Cost (April 2026, £2.50 rise) |

£2.50 rise increase (%) |

|

3GB |

£16.00 |

£17.02 |

£17.80 |

£18.50 |

13.51% |

|

10GB |

£17.99 |

£19.14 |

£19.79 |

£20.49 |

12.20% |

|

20GB |

£20.00 |

£21.28 |

£21.80 |

£22.50 |

11.11% |

| Unlimited (Plus) |

£21.99 |

£23.40 |

£23.79 |

£24.49 |

10.21% |

|

40GB |

£21.99 |

£23.40 |

£23.79 |

£24.49 |

10.21% |

|

50GB |

£23.00 |

£24.47 |

£24.80 |

£25.50 |

9.80% |

|

100GB |

£24.00 |

£25.54 |

£25.80 |

£26.50 |

9.43% |

|

150GB |

£25.99 |

£27.65 |

£27.79 |

£28.49 |

8.78% |

| 10GB (Ultimate) |

£26.49 |

£28.19 |

£28.29 |

£28.99 |

8.62% |

|

250GB |

£27.00 |

£28.73 |

£28.80 |

£29.50 |

8.47% |

| 40GB (Ultimate) |

£30.49 |

£32.44 |

£32.29 |

£32.99 |

7.58% |

| 150GB (Ultimate) |

£34.49 |

£36.70 |

£36.29 |

£36.99 |

6.76% |

*CPI of 2.5% based on January 2024 figures

According to a YouGov survey, 61% of consumers thought that the new pricing model was easier to understand, although half of consumers still wanted contracts to display percentages – something that was explicitly banned by the rule change.

The February 2025 study of actions people took in response to price rises found that only 34% of customers check their contracts.

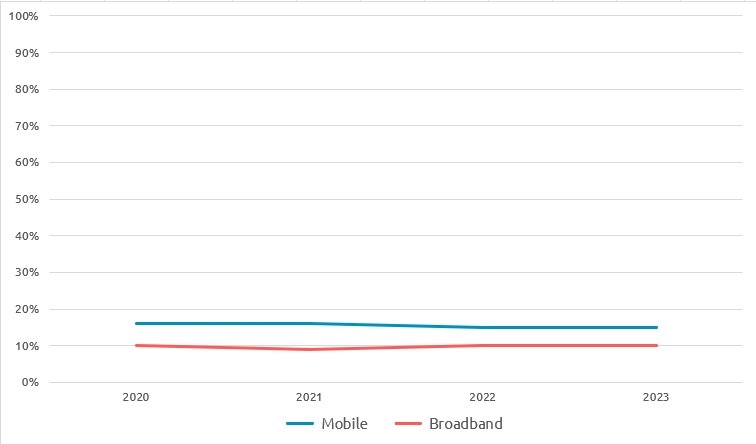

In fact, most UK customers don’t bother to switch, even when prices rise or when they’re unhappy. Consumer inertia or limited alternatives mean that switching rates remain low, despite price increases. Many customers resign themselves to price rises, rather than seek out another provider, with only 15% of customers changing provider in 2023.

Meanwhile, a KPMG study found that only 35% of consumers would leave their provider once their contract ends if prices were to rise. After all, if everyone is increasing their prices, what’s the point? Churn is a hassle for consumers, not for telcos.

Together, these figures show a market where low switching rates and low contract awareness reduce the commercial risk of mid-contract rises.

Annual consumer switching rates

In response to criticism, O2 said: “A price increase equivalent to 8p per day is greatly outweighed by the £700 million we invest each year into our mobile network, with UK consumers benefitting from an extremely competitive market and some of the lowest prices compared to international peers.” Indeed, 8p per day doesn’t sound like much, but with a mobile base of 20+ million customers, even a marginal rise earns tens of millions in extra revenue.

For operators, these consumer dynamics coincide with their own rising costs and tightening margins.

Inflationary pressures from staffing, energy, and network investments are expected to reduce telco EBITDA margins by 3-5 percentage points over the next two years. So with inflation becoming harder to predict, many operators are now looking at fixed price increases to protect their margins.

VMO2’s financial statement for 2024 notes that: “We are subject to inflationary pressures with respect to certain costs. Any cost increases that we are not able to pass on to our subscribers through rate increases would result in increased pressure on our operating margins.”

Liz Kendall, Secretary of State for Science, Innovation and Technology, wrote an open letter to Ofcom, asking it to once again revisit rules around mid-contract price rises. She wrote: “they are against the spirit of your previous changes on pricing, and all the more disappointing given the current pressures on consumers.”

Martin Lewis, founder of MoneySavingExpert, said the move “makes a mockery of Ofcom's new 'pounds and pence' consumer protection regime,” warning that “now O2 has opened the door to this behaviour other mobile firms will feel less worried about following suit.”

And open the door it has. Other providers now seem to be tacitly colluding on price rises, with Three raising monthly charges by £1.50, while Vodafone is increasing its SIM-Only basics plans by £1.50 and other SIM-only products by £2.50 for new customers, and TalkTalk are raising prices by a flat £4.

When all major operators apply similar in-contract rises, the risk of losing customers is low because no competitor is clearly undercutting. If all major players adopt similar fixed increases, relative prices remain stable, reducing incentives for switching. Inevitably, these changes hit those who can least afford it the hardest.

Ofcom has also come under fire for its toothless response, which came to little more than a statement complaining that the price rise “goes against the spirit of our rules.” Even after the ban on inflation-linked rises, providers can still increase prices by a fixed amount, as well as redefine plan tiers, change bundles, and raise out-of-allowance charges such as roaming.

Relying on telcos to govern themselves through an honour system has resulted in customers paying more for services than they otherwise would, while the added transparency brought by the new rules is all for naught if CSPs can still change their minds.

The industry’s pricing strategies and regulatory interactions point to a market of ongoing uncertainty; raising prices and relying on consumer inertia to maintain margins is, in this instance, the rational option, if not the fair one. Telcos should offer customers simple, comparable tariffs and transparently distinguish between meaningful investment costs and revenue extraction.

Could Ofcom insist on fixed prices for the full contract term, banning mid-term increases entirely? It could also step in more decisively when operators raise prices that go “against the spirit” of the rules.

But without such intervention, the “pounds and pence” model risks becoming little more than a different route to the same outcome: predictable annual price hikes with limited consumer protection.

Update [27/11/25]: Rachel Reeves, UK Chancellor, and Liz Kendall, Secretary of State for Science,

Innovation and Technology, have written an open letter requesting that Ofcom "review the suitability of the current 30-day notice period rule."