Past its prime: what to do with legacy telecoms infrastructure?

Shutting down legacy telecoms services is a necessary task on the path to modernisation, but risks cutting vulnerable users off. How can telcos continue to innovate without leaving customers behind? And why are many telcos shuttering their 3G networks before 2G?

In March 2016, a rural train station in Hokkaido, Japan closed after years of only serving a single passenger. A girl living in a nearby village depended on the service to get to school every day, so Japan Railways vowed to keep the station open until she graduated, a promise they kept.

This quaint tale raises the question: in the rush to modernise infrastructure and services, how long is it viable to keep old services going for the benefit of a dwindling number of users? And what to do with them once they’ve outlived their purpose?

While converting thousands of the UK’s old red phone boxes into everything from mini-libraries to coffee stalls makes a lot of sense, the same can’t be said of the underlying tech.

Look at the impending withdrawal of the UK’s copper-based PSTN and ISDN telephone networks, and their gradual replacement with fibre. Would (or could) a telco keep an entire network running for a single user?

In May, Openreach issued a “stop sell” notification in the trial area of Mildenhall, Suffolk, with new or upgrading customers now only being offered all-digital phone and broadband services. This “stop sell” order is due to extend across the rest of the UK by September 2023, ahead of the nationwide upgrade to fibre, with the copper network set to be closed in 2025.

Many customers are unlikely to miss the old networks though, as 40% of UK households have foregone a landline connection altogether, whilst a quarter of those that still do haven’t even bothered to plug in a handset, their unwanted connections undoubtedly coming as part of a broadband, mobile and/or TV package.

Digging into the numbers shows a stark generational and geographical difference, with 95% of over-65s still using a landline versus only 52% of 18–24-year-olds; whilst 83% of rural households have a landline, compared with 65% in urban areas.

Many elderly, isolated users may find themselves suddenly cut off without adequate communications explaining the copper shutdown, or the help they need with the process of switching. But as the generations shift and the elderly become more tech-savvy, is clinging on to these legacy services for the sake of older customers becoming an increasingly redundant course of action?

The situation is more complicated in other countries, such as the Netherlands, where T-Mobile is taking infrastructure owner KPN to court in the hope of halting the shutdown of the nation’s copper network in 2023, arguing that the process was announced too late for T-Mobile to migrate all its customers to fibre.

For businesses, private circuits are on their way out too; BT’s Analogue, Kilostream and Featurenet services were officially to be closed in 2020 – perhaps, at that time, no-one noticed that their offices were suddenly disconnected. But with hundreds of customers still using these services, an Emergency Overrun Service (EOS) is now in effect until the end of March 2023.

Currently, there is no program to recover any old equipment, such as copper wiring – as the stripping of Huawei equipment from UK networks is proving, however, this isn’t work to be taken lightly. Removing large cables could free up space within ducts, though any cables clad with insulation are unlikely to be worth much, but with a great deal of cabling soon to be going spare, certain unscrupulous individuals may take it upon themselves to remove it free of charge.

As traditional landline networks are put out to pasture, telcos are also looking to shutting down their older mobile networks too.

Initially, 4G was unable to support voice alongside the enhanced coverage it provided, giving 2G a reprieve. Since the arrival of VoLTE though, its days have been numbered.

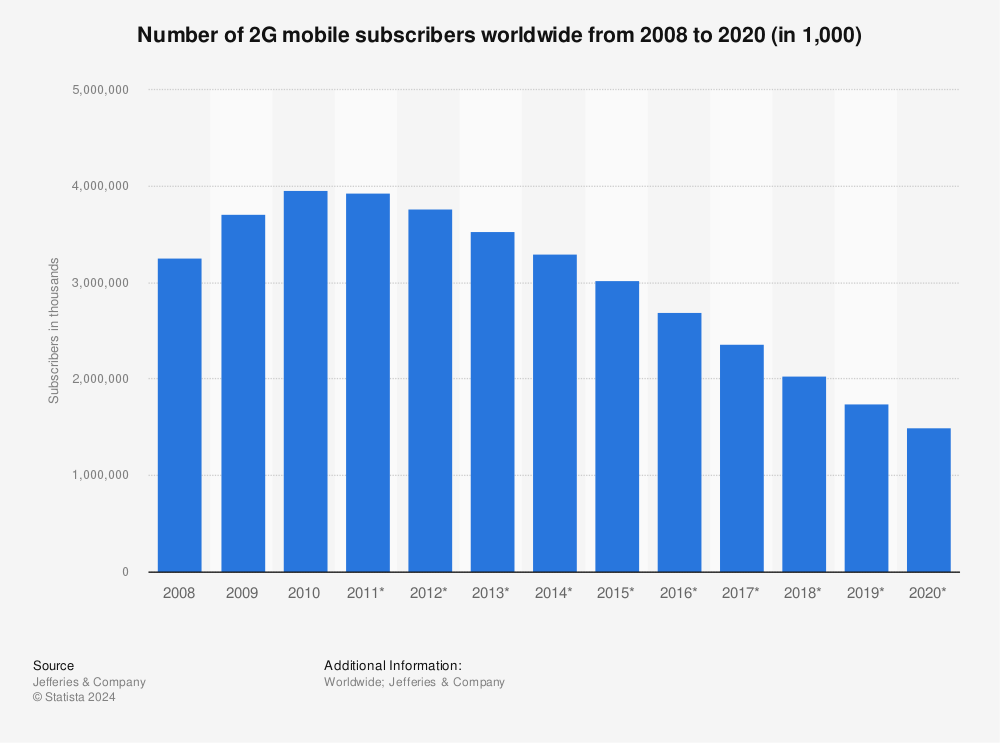

To save on costs and free up spectrum, many 2G networks are being phased out, a fate that is soon to also befall 3G. However, some CSPs are still holding on to 2G as a low-power back-up network, particularly for rural areas, while 3G spectrum gets given over to 4G and 5G.

Andrea Dona, Chief Network Officer of Vodafone, said: “2G will have a longer lifetime, a longer role to play, especially when it comes to the Internet of Things [like smart meters, for example] where you actually don’t need speed, you don’t need the capacity, you just need it to be ticking away in the background with low power.”

A few CSPs were quick to shutter their older networks, such as Japan’s NTT Docomo, who actually brought forward their 2G closure from December 2012 to March 2011, but most are only just getting around to it now.

The UAE’s Telecommunications Regulatory Authority (TRA) will shut down 2G services in 2022, while South Korea, which now boasts some of the highest 5G penetration in the world, was due to close its final 2G network earlier this year. Clogging the process was Korea Telecom being denied permission by the Korean Communications Commission, as 5% of its userbase (810,000 people) were still using 2G.

Meanwhile in the USA, AT&T aims to close its 3G service in February 2022, in a move that will affect 2.7% of its customers – joining the likes of Vodafone, Telefonica, and Deutsche Telekom who have already closed their 3G services.

In a filing to the FCC challenging the move, however, Zonar Systems has warned the shutdown will have far-reaching consequences for other services that still depend on 3G, causing “irreparable harm” to customers and services, citing in particular emergency, freight, utility and construction vehicles that still depend on the network for logistics and navigation.

Passengers in San Francisco got a taste of what may come to pass when these networks close when, back in 2017, AT&T turned off the 2G network that powered NextMuni, a bus and train schedule prediction app, taking the service offline for several weeks.

Some six million home security alarms employing 3G to connect to emergency services will also be affected, with COVID hampering the production and distribution of replacement tech.

Layers of legacy infrastructure combined with the hidden tech still dependant on 2G and 3G mean that just pulling the plug isn’t a viable course of action.

Operators must anticipate when the cost of supporting the remaining 3G and 2G networks becomes unviable and incentivise users to move to newer services, allowing them to reallocate 2G and 3G spectrum to 4G and 5G networks. As demand declines, another option is that operators could combine existing 2G and 3G bandwidth in a single network through dynamic spectrum access, until the time is right to close them for good.

As with all tech, eventually, progress will overtake copper networks, 2G and 3G, and they’ll inevitably be retired as coverage of newer generations continues to grow and customers seek the fastest connections they can get.

It’s up to telcos to manage the process – involving timely customer communications and a smooth upgrade procedure – without frustrating customers or dragging out the switchover process.

Update [09/01/2024]: BT has launched a pilot scheme to convert old street cabinets into electric vehicle (EV) charging points, beginning in East Lothian, Scotland rolling out across the UK in the “coming months.” If successful, the scheme could see 60,000 street cabinets across the country upgraded.