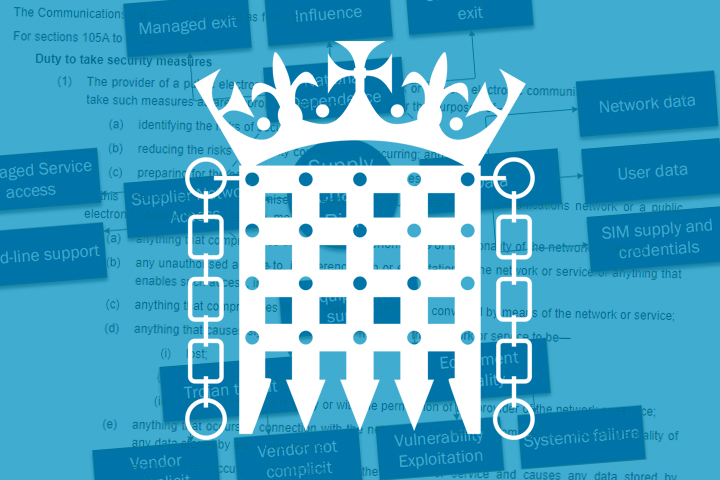

Unpacking the Telecommunications Act 2021

The UK’s new Telecommunications Act places the burden of responsibility for network security on CSPs. What are the implications for telcos and their equipment procurement?

The UK’s new Telecommunications (Security) Act 2021 was enshrined into law on 17th November by Royal Assent.

In contrast to the wide-reaching implications of previous bills – such as the Communications Act 2003, which saw Ofcom established – this bill focuses on voice and text communication services, and the security of telecom networks.

The bill imposes new obligations on CSPs – or providers of electronic communication networks and services (PECN / PECS) – while giving Ofcom further powers in its legislative arsenal to monitor and ensure compliance with these new rules.

Then Digital Secretary Oliver Dowden said the bill would give the UK “one of the toughest telecoms security regimes in the world and allow us to take the action necessary to protect our networks.”

The bill was brought to the Commons by Matt Warman MP, then-Parliamentary Under-Secretary for the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), formerly a member of the Science and Technology Select Committee and Telegraph tech journalist, with a keen interest in 5G cybersecurity and a wariness of foreign interference.

Ofcom now has the power to demand an explanation from any CSPs it believes to be in breach of the regulations, and can levy fines of up to £10 million or £50,000 per day if a provider fails or refuses to explain a failure to follow the rules. Per the new powers, further fines of up to 10% of turnover, or £100,000 per day for ongoing infractions can also be imposed.

Furthermore, the Secretary of State now has the power to outline specific measures to identify, prepare for and reduce the occurrence of security compromises.

The bill also gives provision for any individual affected by a breach of duty to sue the CSP responsible. These rules will apply to all providers of all sizes, divided into three tiers per the legislation.

But the bulk of the Act is on introducing new powers for the Government to manage the risks posed by “high-risk vendors” such as Huawei and ZTE. With “designated vendor directions,” they can impose restrictions or outright bans on equipment and services from certain suppliers in the interests of national security, while Section 105Z25 of the Act prevents CSPs from even discussing the terms of any directions.

In fact, a ban on buying new Huawei equipment had already come into effect on 31st December 2020, with all existing Huawei equipment to be removed from critical 5G network infrastructure by the end of 2027. However, such is the penetration of Huawei tech already used in the UK’s networks, that removing it could lead to service failures, according to BT boss Philip Jansen.

Despite no providers being named explicitly in the new bill, Huawei is currently the only high-risk vendor singled out by the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), who argue that Huawei could, per China’s National Intelligence Law 2017, be compelled to “cooperate with the state intelligence work in accordance with the law.”

Though the oversight board’s 2021 report concluded that there was no evidence suggesting there are any backdoors in the UK’s virtualised networks, it found serious security issues with user-facing software, and that none of the improvements suggested in its 2020 report had been implemented (COVID notwithstanding).

GCHQ head Jeremy Fleming warned that 5G technology “is implemented in a way in which we can't assure its security,” while blaming the West for not investing in its own infrastructure. According to Victor Zhang, Huawei’s Vice President, though, “This decision is politically motivated and not based on a fair evaluation of the risks.”

Nevertheless, most concerns as to Huawei’s security seem to be technical rather than political. The situation is a case of Hanlon’s razor – are these vulnerabilities in Huawei networks the product of malice or incompetence? Perhaps this ambiguity is the point.

Though the political motivation to diversify the supplier network is not easily untangled from the practical side (with the twin crises of COVID and the global supply chain shortage also impeding 5G rollouts), being dependent on any single supplier would present a significant risk to service delivery for millions of people.

And whilst the new bill appears to be a positive one, it only begins to scratch the surface of network security legislation, while placing a highly politicised additional duty on CSPs. Adopting a proactive approach to security process and reporting now will be necessary to ensure they remain compliant when further legislation comes into force in the future.