The psychology of subscriptions

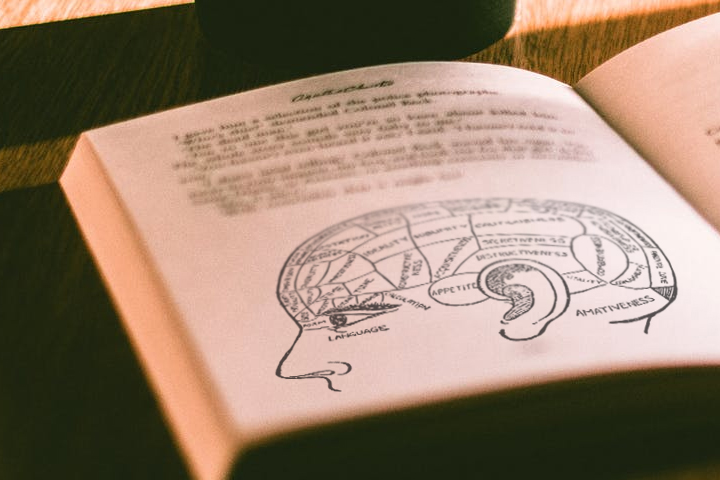

Consumer psychology won’t let you brainwash customers into becoming loyal consumers, but it offers important lessons for subscription companies in designing their products and customer experience. We take a deep dive into the psychology of subscriptions, and try to separate the useful hacks from the useless hokum.

In his book How Customers Think: Essential Insights into the Mind of the Market, Harvard Business School professor Gerald Zaltman states that “About 95% of all thought, emotion, and learning occur in the unconscious mind.” It stands to reason then that recurring subscription-based payments and purchases would mesh well with this understanding of the human mind, taking the transaction and the act of paying into a more abstracted realm and disrupting the usual thought process behind making payments.

For decades, businesses have been turning to psychology to increase sales and become more than a mere peddler of wares in the eyes of their customers. The changing media landscape in the aftermath of the Great Depression through to the end of the Second World War fuelled interest from the burgeoning worlds of psychology and advertising, and in 1960, the American Psychological Association established a Consumer Psychology Division, dedicated to getting inside the minds of the increasingly monied consumer class.

But the rise of e-commerce, recurring payments and the digitalisation of goods and services have changed consumer behaviour considerably, in particular their approaches to purchasing. When buying subscriptions versus ordinary one-off transactions, consumers think differently, and pivoting your approach towards this altered customer attitude is essential to making the most of new market opportunities.

Pricing

Enticing your prospective customers into entering a recurring payment pattern involves more than just settling on an appealing price.

Pricing your goods or services with a figure ending in .99 – or charm pricing – is one of the oldest psychological pricing tricks in the book, yet the origins behind this sales tactic may in fact lie in retail loss prevention rather than devious psychological trickery; to prevent any unscrupulous employees from simply pocketing the money, charm pricing forced them to open the till and give change to the customer.

In fact, research suggests that customers may prefer paying for amounts costed in round numbers, with many considering a .00 price tag to be a mark of quality – perhaps a case of consumers getting wise to a particularly ubiquitous tactic, as now reflected in the majority of providers’ price schemes. Nevertheless, there are still some subscription businesses sticking to their guns with charm pricing models, notably the big names of streaming such as Spotify and Netflix.

Anchoring bias occurs when customers factor in previous, often irrelevant information into their decision-making; if a customer sees a similar product or service to yours that costs $500, then see that yours costs $300, they’ll be prone to consider yours as “cheap” in comparison, despite its hefty price-tag.

In 1985, economist Richard Thaler posited that people treat their finances depending on factors such as the money’s origin and intended use – a phenomenon he dubbed “mental accounting”. With mental accounting, the fungibility of money changes, depending on its source and intent.

With subscriptions, your customers will be drawn towards seeing the costs in instalments, rather than the total amount they may end up paying. John Gourville argued that “temporal reframing” – or the pennies-a-day (PAD) strategy – breaking down the costs to small, daily amounts, is equally effective. A great example of this is digital newspaper subscriptions which are promoted in pennies or cents per day, even though you are typically billed monthly.

When enticing your customers, side-stepping the price matter altogether is also a strategy worth considering; results from a 2009 study showed a significant reduction in spending when monetary terms (such as ‘‘dollars’’) or currency symbols were used. Instead, a “time vs. money effect” focusing on the time aspect develops a personal connection with the product or service and its use, instead of focusing on the transaction – your customers will react more positively to the time they will spend or save with a product than hearing a financial argument.

The customer

When it comes to subscriptions, two areas of the brain compete for control when a customer tries to balance short-term and long-term rewards – the rational, forward-thinking side, and the irrational, emotionally-driven side.

A study by psychologists at Harvard and Princeton found that participants who are offered either a small pay-out immediately or a larger pay-out tomorrow are more likely to choose the smaller amount, but, if given a choice between the small amount in one year or the larger amount in a year and a day, people would tend to choose the higher amount.

The Cashless Effect is the greatest friend of any e-commerce business; customers are more willing to part with their money if they aren’t handing over any notes or coins. Unlike many day-to-day transactions, subscription payments often take place without the customer even realising a payment has taken place. Payment by card is abstracted and, with credit cards, atemporal, unanchored to a particular moment in the decision-making process. Once they’re over the hurdle of signing up to your product or service, the monthly charging fades into the background as automated recurring billing steps in.

“Credit cards effectively anesthetize the pain of paying,” said George Loewenstein, Carnegie Mellon professor of social and decision sciences. His study into the effects of spending on the brain found that when subjects saw prices that were too high, the insular cortex, the same region of the brain that handles functions including emotional processing and pain perception, would flare up. If your customers use first and are billed later (postpaid), then the transaction becomes more of an ordeal for them and they are more likely to query the charges; but when they pay upfront (prepaid), they focus on the benefits, numbing this pain of paying.

In Arkes and Blumer’s landmark 1985 study into the sunk-cost effect, it was shown that consumers feel compelled to use products they’ve paid for to avoid feeling that they’ve wasted their money. To demonstrate, Arkes, a lecturer at Ohio University, asked his students to imagine that they’d accidentally purchased tickets for two ski trips on the same weekend: a more enjoyable trip costing $50, and a less enjoyable $100 trip. How would they choose? More than half the students opted for the less enjoyable but more expensive $100 trip; the sunk cost mattered more than their enjoyment.

Considering the psychological make-up of your target audience is also important. As we’ve previously covered, millennials and Generation Z in particular are increasingly defining themselves based on the products they consume, especially when it comes to the corporate social responsibility on display by service providers.

Your customers are equally prone to spend more when feeling nostalgic: “We found that when people have higher levels of social connectedness and feel that their wants and needs can be achieved through the help of others, their ability to prioritize and keep control over their money becomes less pressing.”

Gourville, once again, and Dilip Soman, building on Thaler’s work, found that bundling of goods leads to a disassociation of a transaction’s benefits from its costs and decreases a customer's likelihood of consuming a paid-for service. In another ski-based study, they demonstrated that subjects given a bundled four-day ski pass were less likely to go skiing on the final day, as opposed to those given four one-day passes.

However, while unused products or services can benefit the providers in the short term – all the income for none of the expenditure – if customers wake up and unsubscribe, then businesses lose out on income and reputation.

The purchasing experience

Businesses can make purchasing decisions easy for customers by incorporating “nudges” to aid them in their choice. Website designers may employ the Centre-Stage Effect, for example, presenting their most preferred product in the centre of a side-by-side display; in these circumstances, customers will typically choose the middle option. You don’t even have to be covert with such influencing behaviours – recent studies suggest that “nudge transparency” has no impact on how effective they are, even when employing well-known nudges, such as the Centre-Stage Effect.

According to Stefano DellaVigna & Ulrike Malmendier’s study of US health clubs, members who chose to pay a flat monthly subscription ended up paying more on average per use than if they paid for individual visits. Payments made at or near the time of use draw attention to the cost, and thus increase the likelihood of consumption, while payments made prior to or after the transaction decrease the likelihood that the customer will use the product or service. By favouring established patterns of behaviour over new ones, however, no matter how counterintuitive or detrimental they may be, the customer may find themselves falling into a state of cognitive inertia.

Sometimes, when purchasing a subscription, the consumer may be their own worst enemy when it comes to decision-making; the Paradox of Choice, outlined by psychologist Barry Schwartz in his 2004 book of the same name, dictates that, when faced with a large number of options, consumers are in fact less likely to make a choice, leading to decision paralysis.

While subscriptions can, in many cases, allow for a vast amount of granular control of the service they receive, customers can become vulnerable to choice paralysis. People are, in fact, more likely to act when faced with fewer options.

To demonstrate this, researchers from Columbia and Stanford University set up a jam stall at a food market with 24 kinds of jam, to which shoppers showed interest, but of which few made purchases. On another day, at the same stand at the food market, they offered only six choices of jam and found that shoppers were more likely to make a purchase from the smaller selection.

Psychology doesn’t offer any guaranteed hacks for increasing your funnel or growing revenues; these studies, having been undertaken under controlled circumstances that may be difficult to replicate outside of laboratory settings, shouldn’t be taken as gospel in regard to how you run your subscription business. However, it does offer a set of best practices, backed up with quantifiable results, on how to influence your customers to achieve the best possible business outcomes.

After all, your business is dealing with real people, not subjects in a lab.

Cerillion’s subscription market experts are ready to guide you through the world of subscriptions with their years of industry experience. Find out what our dedicated team can do for you today.