How can value-based pricing make data usage really count?

Should an hour of video or game streaming cost your customers more than an hour of WFH teleconferencing? Value-based pricing is the key to growing revenue with 5G – how can telcos price their services accordingly?

What weighs more? A kilogram of feathers, or a kilogram of steel?

So what costs more – a gigabyte of industrial IoT data, or a gigabyte of video streamed from YouTube?

Just because two streams of data are functionally the same doesn’t necessarily mean they have the same value.

Value-based pricing has been around for, well, the entirety of human history, setting prices for products and services based on who they are for, their needs and their means, rather than the simpler cost-plus model.

In the telecoms realm, though, there’s been little differentiation in the price of connections, charging only by duration of calls made, number of texts sent, or volume of data used, because no effort has been made to distinguish the value of services to enable any pricing differentiation.

Connectivity may now be considered the fourth utility, but should it be priced as rigidly? Gas and electricity are, as we’ve been so dramatically reminded of lately, priced on a cost-plus basis, reflective of wholesale costs, however data doesn’t have to work in the same way.

Pricing should reflect the amount that consumers are willing to pay for the value delivered by a product, meaning those who can pay more do pay more, while those who are unable to won’t be completely priced out. Think of air travel – those who can afford to can buy a first class or business class ticket, while those unable to afford it can travel in economy class. All passengers get to the same destination at the same time, but their experience during transit is the differentiator.

Thanks to the advanced features of modern BSS/OSS systems, it’s never been easier to implement variable pricing schemes and tariffs across both consumer and business segments.

Value-based pricing is broadly defined by four factors:

The customer

As different customer segments are willing and able to pay varying prices for largely the same product, the question of who is paying massively determines how a product or service is priced.

For those with more cash to splash, premium packages provide the same core offering, supplemented by some bonuses. At the other end of the financial scale, social tariffs are available for customers in receipt of benefits or other government support.

However, just how companies determine this segmentation is another question.

Ofcom recently investigated personalised pricing, but consumers considered it “unfair,” there being no baseline from which to judge whether what they were getting was now a good deal. Group targeting is less invasive, requiring less information from individuals, but isn’t as effective as individual targeting – perhaps less accuracy is the price to pay for a modicum of customer privacy.

Surveys suggest that consumers are willing to pay more for services if they see the additional value in doing so. Conversely, as so many customers pay for more data than they use, many would likely leap at the opportunity to have their bills adjusted to reflect their use more accurately.

The product

Just as different customers demand different prices, variants of the same product or service call for a varied pricing scheme.

How much of that data is consumed in particular use cases may, however, warrant more consideration when it comes to pricing. High-definition video and mobile gaming delivered over high-speed 5G for reliable consistency and low latency may warrant a heftier price than similar services delivered at a less reliable rate over 4G.

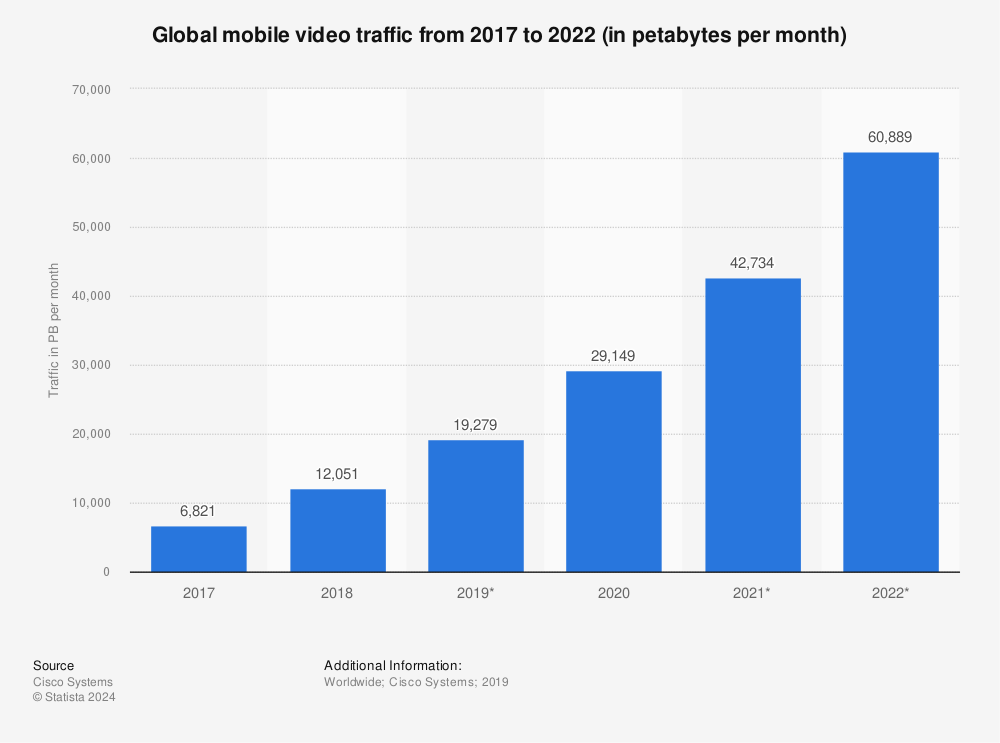

It is possible to compartmentalise, for example, video streaming data, and charge at a different rate than browsing data. As video traffic in particular continues to grow at a remarkable pace, increasing by 42% this year versus last, value-based pricing can prove to be a powerful generator of revenue here:

Bundling the product with extras such as a pay TV, landline or a streaming deal is a tried-and-tested quick win for telcos looking to add some polish to their product; on the flipside, providers may look to zero-rating as a value-added (or should that be removed?) service, letting customers access proprietary services, such as customer support, at no extra cost.

An interesting example is EE’s Stay Connected service, which keeps customers online with a basic service even when they’ve run out of credit. If you use up your monthly data allowance, you’ll automatically switch to 0.5Mbps speeds, which is fine for instant messaging, but not much else. To go back to full plan speeds, you can buy a daily or monthly data add-on or wait until your bill cycle refreshes.

Other providers have gone one step further, zero rating streaming and social media platforms on their networks (though this hasn’t been without its controversy), and online support for low-income customers, as O2 did early in the COVID-19 pandemic, making accessing the NHS, Citizens Advice, and the mental health charity Mind free of charge for its customers.

The time

The perceived value of a product can vary based on when it’s being used, and the effects of that on supply, demand and other factors – think of the price of umbrellas being raised while it’s raining, or surge pricing for taxis during busy times on the road.

For telcos, peak times for data could call for a higher charge rate, encouraging heavy data users to use off-peak times just as some utility providers do – but should these peak times be defined as during the day for work purposes, during the evening “internet rush hour” between 7pm and 9pm, or even a dynamic approach based on actual supply and demand?

Telcos could equally provide WFH-ing customers with packages prioritising their working needs during the day – for example, a symmetric service providing the same download / upload speed during working hours. But if a telco opted to charge customers more for this, who covers the bill? Would customers be so keen on paying more, or would employers subsidise the added cost?

The brand

In this instance, prices are set based on the prestige of a product, be it real or perceived. A particular product or service may be deemed to be of higher worth to confer a sense of value, or lower, to be more accessible to more cost-conscious customers, such as “value brands” from supermarkets.

Some customers may expect to pay less for a small, local altnet as opposed to a major MNO, even if there’s little differentiation in the quality of service offered. Equally, discounts may look enticing to some customers, but may also make a product seem less desirable to others.

Quality of service can even add to the value of other goods and services as, for example, estate agents move to include broadband and mobile coverage on property listings.

The key to value-based pricing is offering the best possible balance between vertical and horizontal differentiation. This is a case of functionality versus form; for vertical differentiation, customers rank products based on tangible qualities, such as price, while in horizontal differentiation, they look to more abstract factors, such as brand reputation or simple personal preference. A nice example can be found with WhatsApp’s switch to a conversation-based pricing model on its Business app.

Some consumers, however, may fear that value-based pricing will mean that someone else might get a better deal than them – or worse yet, that they have more to lose than gain from lower prices.

Creating many variations of the same product at scale is sure to incur an extra cost without a modern, automated BSS/OSS to improve customer experience and generate additional revenue through smarter pricing decisions.

Nevertheless, without a value-based pricing strategy in place for the 5G era, telcos risk missing out on a great deal of potential profit from increasing demand for a wider range of services.

Ensure that your telco is equipped to handle value-based pricing with Cerillion’s Enterprise Product Catalogue and Convergent Charging System. Speak to one of our experts to learn more.