Top Telecom Anti-Trends for 2026

You’ve likely already seen the top telecoms trends for 2026, with analysts and marketers gushing over the latest AI updates and satellite launches, to mention just two. So this year, we’re taking an alternative approach and considering which so-called trends are, despite all the hype, unlikely to succeed in 2026?

The telecoms sector begins 2026 with a widening gap between industry narrative and commercial reality, as analyst reports, vendor keynotes, and conference stages continue to trumpet a familiar set of next big things. But operator financials, deployment data and adoption metrics all tell a different story.

So instead of our usual look at what we think will be the major industry trends for the year ahead, this time, we’re looking at what trends we think will under-deliver, relative to expectations, in 2026.

These anti-trends are not predictions of failure. Rather, they highlight areas where expectations, investment narratives and timelines have raced ahead of what technology, economics and customer demand are realistically able to support in the near term.

Satellites won’t be a mass-market broadband alternative in 2026

The hype for low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellites like SpaceX’s Starlink reached fever pitch in 2025, with promises to deliver gigabit internet to every corner of the globe and render terrestrial networks obsolete. However, this hysteria masks just how small the service revenue base will be for now.

It’s true that 2025 saw several deals between telcos and satellite providers for direct-to-device (D2D) services, with SpaceX buying $17 billion of spectrum for D2D services and submitting a trademark application for Starlink Mobile.

But, the reality is that, with current technology, it’s not possible to build a network capable of high-density connectivity from space. When fully operational, D2D will largely only support customers in remote areas, connections to vehicles on the move, or complement traditional terrestrial mobile networks as an emergency backup. For the vast majority of users, terrestrial infrastructure and fibre will always win out.

Current handsets simply can’t be in constant contact with satellites orbiting at hundreds of miles per hour above Earth all day, especially in dense urban environments with high concentrations of users transmitting at max power, greatly increasing the risk of interference.

This isn’t stopping SpaceX from trying to gobble up more funding though, having lodged complaints that too much investment is going into fibre internet providers in Virginia and Louisiana, instead of on guaranteed service availability for satellite providers.

SpaceX wants around 49,000 of its satellites in orbit, greatly raising the risk of orbital collisions. According to the recently-launched Collision Realization And Significant Harm (CRASH) Clock, which forecasts the timescale for collisions if there are “no satellite manoeuvres,” Starlink’s mega-constellation could see a collision every 5.5 days, down from 164 days in 2018. Furthermore, in a letter to the FCC, Viasat warned that Starlink’s plans “would generate insurmountable interference risks for other spectrum users and the customers they serve.”

So, satellite broadband remains largely unfeasible at scale. Not to worry though – as data devours the world, and the demand for data centres greatly outstrips what can be delivered today, data centres in space are predicted to be the next growth area, according to some.

Putting data centres in orbit sounds revolutionary; near-limitless solar power, no weather interruptions, and low, low temperatures in space – right? Space is cold, yes, but space is also a vacuum – like a Thermos – meaning there are no air particles to pull heat away via convection. Space infrastructure like the International Space Station (ISS) depends on massive radiators, not to heat the space station, but to radiate heat away.

However, the Stefan-Boltzmann law dictates that you can't radiate a sufficient amount of heat from a small surface. So for just one satellite data centre, you would need a massive radiator, perhaps as large as several square kilometres, to handle the power needed.

Nevertheless, the biggest problem is sending data back to Earth; satellites can only handle 0.5-10 Gbps, and even the fastest laser links top out at 100-200 Gbps, far below the speeds that terrestrial data centres require. Therefore, space compute makes sense only for processing of space-based services (e.g., satellites that must process sensor data before downlink). For general data centre use, Earth still wins on power, cooling, maintenance, and cost.

Key takeaway: For telcos, satellites remain a coverage and resilience tool, but technical and economic constraints mean they are not a substitute for terrestrial networks or a meaningful new revenue engine in 2026.

The growing cynicism around GenAI and its capabilities will continue

While the exuberance around AI remains high, 2025 saw the first cracks forming in the hype bubble, and the financial viability of GenAI versus the scale of investment needed is the central question for 2026.

OpenAI’s GPT-5, which launched last year, was hyped up to deliver PhD-level cognition, but it didn't deliver on the promise. Now, despite $30-40 billion of investment, MIT says that 95% of organisations are seeing “zero return” on their investments, while separate tests from last year found that AI agents failed to complete tasks 70% of the time.

What it has brought instead is higher prices for GPUs, as OpenAI has bought up 40% of global DRAM output, causing prices of consumer gear to triple or quadruple. However, all this hardware is now sitting unpowered because the electrical infrastructure to support it doesn’t yet exist, if ever, and will likely be obsolete in no time.

Despite its attempts to restructure as a for-profit enterprise, OpenAI has made no profit to speak of from its 800 million weekly users, making a net loss of $11.5 billion or more during Q3 2025, effectively losing money on every user, free or paid. Having lost its first mover advantage, and fast ceding ground on market share, OpenAI could run out of cash as soon as next year.

When one investor asked Sam Altman how the company, with annual revenues of around $13 billion, can afford its $1 trillion of commitments, Altman replied:

🚨 Brad Gerstner, an OpenAI investor, asks Sam Altman how a company with $13B in revenue can afford $1.4T in commitments. Altman’s reply? “Happy to find a buyer for your shares.” Translation: No answer. Very concerning. 🚩 pic.twitter.com/9jJKGw9QbF

— WallStreetPro (@wallstreetpro) November 2, 2025

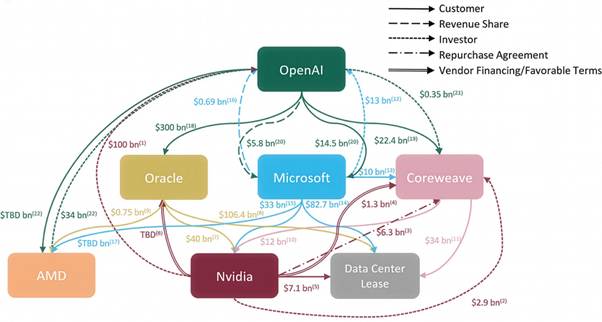

Much of the funding that’s sloshing around is being passed from firm to firm, creating a circular illusion of economic activity; Paul is investing in Peter so Peter can buy GPUs from Paul, so to speak:

Confidence in these firms is also starting to crack; shares in Oracle fell by around 46% from their peak in September (making CEO Larry Ellison, briefly, the world’s richest man) after its largest data centre partner backed out of a $10 billion deal for a new site in Michigan.

Despite hopes that this buildout will, in time, generate enough revenue to cover itself, Bain & Company thinks that investors are $800 billion short in revenue. To break even, AI firms would need to charge users far more than they are currently, or find other ways to extract value from customers. Despite Sam Altman declaring that ads - something he once called a "last resort" - would erode user trust, OpenAI is now testing them anyway:

"I kind of think of ads as like a last resort for us as a business model," - Sam Altman, October 2024 https://t.co/BWHiXPlVFD pic.twitter.com/dw2ywE1pYi

— Tom Warren (@tomwarren) January 16, 2026

The capex mirage is now so massive that it might be the only thing keeping the US out of recession; three-quarters of gains in the S&P 500 since the launch of ChatGPT have come from AI-related stocks, and Deutsche Bank says this “parabolic” spending is now essential to prop up the shaky economy.

As for the downstream effects of GenAI, a “layoff boomerang” is expected in 2026 as many of those sacked in the name of AI-driven streamlining are rehired; 55% of companies that cut staff in favour of automation regretted the move, and many are looking to bring back those they let go, but on lower wages. As for the rest of the workforce, it’s the verdict of Oxford Economics that “firms don’t appear to be replacing workers with AI on a significant scale and we doubt that unemployment rates will be pushed up heavily by AI over the next few years.”

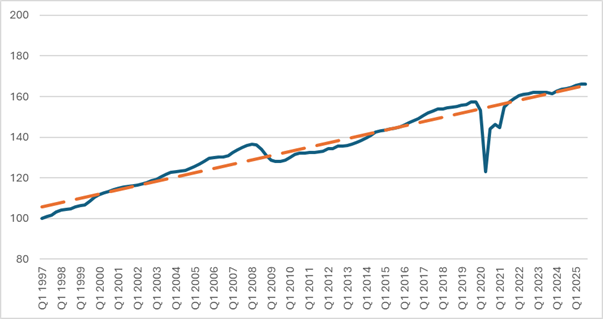

If AI were already replacing labour at scale, productivity growth would be going up. Rather, there's been no notable increase:

UK productivity (output per hour worked)

Forrester believes that “The disconnect between the inflated promises of AI vendors and the value created for enterprises will force market correction.”

As with satellites, the issues we’re running into are hard physics; providers simply cannot generate the energy needed for the data centres to get remotely close to delivering on what these companies have promised. As data centre construction stalls, and AI hardware sits unpowered, it quickly becomes obsolete before it can be installed; “digital lettuce” as David McWilliams calls it.

The reason why RAM has become four times more expensive is that a huge amount of RAM that has not yet been produced was purchased with non-existent money to be installed in GPUs that also have not yet been produced, in order to place them in data centers that have not yet been…

— jatin (@jatinkrmalik) January 9, 2026

GenAI undoubtedly has legitimate use cases in some domains, but what has been promised and what's actually being delivered are not enough to justify such high expenditure.

At the end of the day - where is the great software that GenAI was supposed to create? Satya Nadella says 30% of Microsoft code is now AI-generated, so is AI to blame for a recent Windows 11 patch prevented PCs from shutting down?

Key takeaway: GenAI is more likely to drive cost pressure and strategic reassessment than new telecom revenue streams, remaining a promising but constrained technology that must prove its value against high expectations.

Extended Reality (XR) solutions will remain niche

While virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) remain frequently cited in industry reports as future “killer apps” for telcos, and a driver for 5G/6G investment, is there any substance to these claims?

Consumer adoption and monetisation of VR and AR remain weak, with little indication that they will continue to scale. The form factor of these devices continues to prohibit widespread use; most users don’t want to strap a heavy device that can cause eyestrain or motion sickness to their head to do something they can do on their phone much more easily. Even if they can afford the hardware, they don’t necessarily have the space to use it without moving furniture.

Most VR/AR use, be it for gaming, education or productivity, takes place predominantly indoors, and for good reason; it isn’t wise to be walking down the road while wearing a distracting, peripheral vision-blocking headset.

Major tech players continue to invest heavily, but are reporting large losses in the XR space. Despite renaming the entire company to focus on the metaverse, Mark Zuckerberg is now reportedly planning a 30% budget cut to Reality Labs next year [paywalled] after the ailing department posted a $17.7 billion loss in 2024, strip-mining its resources and redirecting them to AI and wearables.

Though an IDC report forecasts a declining market for VR devices, it also predicts an uplift for mixed reality and extended reality glasses. Meta seems to agree; having popped a bung in their metaverse money tap, they are throwing their weight behind the Ray-Ban Display. Certainly, it fits the description of AR glasses, with its in-lens displays and cameras, yet curiously, marketing collateral doesn’t refer to it as such, preferring the term “AI glasses.”

Some early adopters, or “glassholes,” reviving a term originally for users of Google Glass over a decade ago, have taken these devices to the streets, but the response has not always been positive; many women have complained about being surreptitiously filmed by smart glasses users. In fact, the University of San Francisco was forced to put out a warning to students about a man on campus using Meta Ray-Bans to film students without their permission.

Telcos should not plan for mass adoption of consumer XR to materialise. We might see a resurgence of interest if a major player gains traction, but even optimistic forecasts put mainstream take-up in the latter half of the decade.

Key takeaway: XR is likely to remain a niche technology focused on limited enterprise use cases and brand partnerships, rather than a scaled consumer revenue stream or network driver for telcos.

5G Standalone won’t become a key selling point

For years now, the industry has been hammering home the same narrative: that real 5G hasn’t been tried yet, and true 5G would arrive with Standalone (SA) networks. By the mid-2020s, operators worldwide were expected to have migrated to 5G SA to unlock new features such as network slicing and to monetise new use cases like smart factories. To this end, some operators announced aggressive rollout timelines, and network vendors touted Standalone as the key to delivering on 5G’s lofty promises.

The reality is that 5G SA adoption has been significantly slower and more limited than the early hype projected. A large proportion of 5G networks globally still operate as Non-Standalone, piggybacking off existing 4G cores.

Out of 200+ operators worldwide that have deployed 5G, only 70 have launched 5G SA networks in some form. Furthermore, Standalone coverage is still incomplete in many markets, and operators are only beginning to package and price QoS tiers.

Because the expected new revenue drivers for Standalone – network slicing for enterprises, low-latency links for autonomous systems, massive IIoT – have been slow to emerge, many operators have been hesitant to invest in their core networks.

Consumers don’t care about how networks work, and very few understand the difference between Standalone and Non-Standalone 5G. From a user’s point of view, the experience has remained largely the same; speeds feel similar, prices didn’t drop. They care about whether things work.

A few pioneering operators have launched slicing for first responders or dedicated broadcast slices for live event video feeds, for example, yet these are niche offerings. Furthermore, the really advanced vision of on-demand dynamic slicing via open APIs, where a customer could automatically request a slice with certain QoS, is still in PoC stage and unlikely to go mainstream any time soon.

Key takeaway: 5G Standalone will matter primarily through targeted enterprise use cases and application-specific partnerships, with mass consumer monetisation remaining limited in 2026.

6G is still a long way away

As we continue to wait for 5G to truly happen, work on 6G is already well underway. At the upcoming MWC, 6G is high on the agenda. This is despite the first 6G discussions having taken place at a 3GPP meeting in Incheon, South Korea only in March. Nevertheless, the White House declared in a Presidential Memorandum titled “Winning the 6G Race” that the standard, much like a certain Arctic sovereign territory, is to be “foundational to… national security, foreign policy, and economic prosperity.”

6G as a near-future enabler is at risk of being overhyped. Experts widely agree that 2030 is the earliest realistic timeframe for initial commercial 6G deployments, and even that could be on the optimistic side. While countries like China and South Korea are targeting a 6G capex ramp-up for around then, steep increases in investment without a clear, proven path to fast returns simply won’t work.

The industry hype for 6G glosses over the fact that 5G’s potential is far from fully realised. Worse still, many seem to consider 6G about simply finishing what 5G started.

Given that the boundaries between 5G and 6G are likely to be blurry to many customers and enterprises, it’s not entirely clear what the killer application of 6G will be. Many ideas being thrown around – holographic calls, digital twins, etc. – are speculative at best, and it’s uncertain if there will be significant demand for any of these by 2030.

Or if they can be achieved by other means. Many of 6G’s capabilities might be achieved in late 5G releases or technologies like Wi-Fi and fibre. Some visions emphasise ultra-precise positioning and sensing, but improved positioning can be delivered via 5G.

Operators can’t afford another transitional decade where infrastructure leads but value lags. 6G needs a clean break from 5G, and a focus on a unified core and open standards, ensuring there’s a smooth interworking layer for existing devices, smarter design and sustainable value.

Key takeaway: 6G is a long-term research and standardisation effort, whose impact will only be felt beyond the end of this decade.

Across all of these trends, a common theme emerges: potential, tempered by practical realities.

These anti-trends aren’t just about embracing negativity and rejecting innovation; they’re about rejecting timelines and business cases that don’t survive contact with reality. Hype can inspire, but a clear-eyed view of current realities ensures operators invest wisely and set realistic expectations with both customers and stakeholders.

Success in 2026 and beyond will come from grounded strategies; squeezing real value out of existing capabilities, integrating new and emerging technologies in targeted ways where appropriate, and building the foundations – be it fibre, cloud or skills – that will make future technologies viable.